Shep Messing was sleeping peacefully in his bed at the Olympic Village in Munich, Germany when an urgent pounding at his door woke him up at the ungodly hour of four in the morning.

The U.S. Olympic goalkeeper opened the door and saw a pair of uniformed German soldiers with guns in their hands.

They asked him if he was Shep Messing.

"I took a step back, because I didn't know what was going on, looking to see if I had to defend myself," he said. "And then they showed their credentials. They said, ‘you're Jewish, come with us.’"

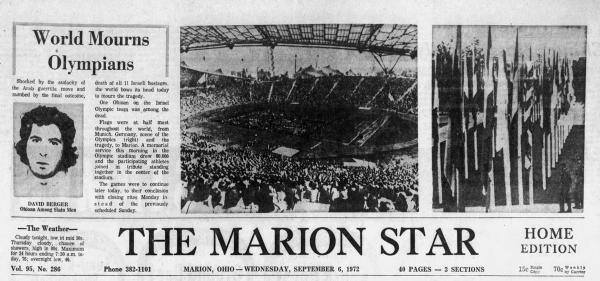

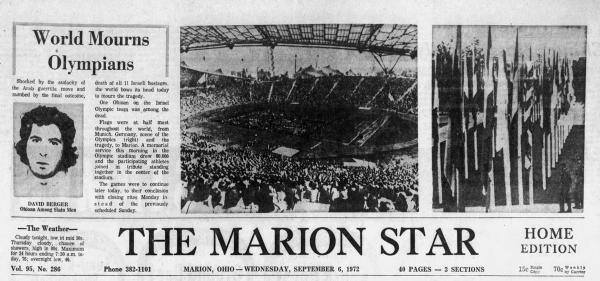

It was Sept. 5, 1972, when a Palestinian terrorist group kidnapped and murdered 11 Israeli athletes and coaches.

"I had no idea what was going on, but [authorities] had taken 12 U.S. Olympic Jewish athletes, Mark Spitz included, into protective custody," Messing said in a recent interview. "Very quickly we found out why, because the Palestinian terrorist group Black September had attacked the Israeli compound. My room was directly across from the balcony of the Israeli complex. One of my friends was there: David Berger, a 27-year-old Israeli American lawyer from Cleveland. I had met him at the Maccabiah games a couple of years before."

It turned into a horrific and unsettling event that changed sports and security forever and ruined that Olympics for many athletes and spectators.

That included Messing, who loved the Olympics while growing up in Roslyn, N.Y. on Long Island.

In fact, Messing's parents held an Olympic-themed party for his 10th birthday.

"I jump, broad jump, track and field, running, catching, throwing as a 10-year-old. No matter what sport, and I didn't have soccer on my radar screen," he said. "I dreamt of playing in the Olympics and that was my 10th birthday party. Of course, it was a home field for me, so I won the Olympics, won the gold medal got the birthday cake.

"You always want to represent your country. As a young boy or girl growing up, the Olympics were a dream. Many years later, it blew my mind that I was invited. After being an All-American in college, I got an invitation to try out for the Olympic team.”

But Messing, who graduated from Harvard University in 1971, reminded us that "there's never an easy path through life."

He missed the first round of tryouts after suffering a badly sprained ankle while playing basketball. Messing got that opportunity - although he hardly traveled first class to the Southern Illinois University, near St. Louis - for the tryouts.

"I'm not recommending this for children," he said. "I had no money, so I hitchhiked from New York to St. Louis. I didn't have enough money for a hotel. So, I slept in the airport. The next day I showed up on the field. I thought I played well. We had a second day of tryouts. I went back to the airport to sleep, showed up the second day. I thought I did extremely well."

He had money for a return trip to New York, but it was too late to catch a flight back. So once again, Messing slept at the airport gate.

The next morning, he bought a copy of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at 5:30 a.m.

"I always turn to the sport page first, and there it was," Messing said. "They had named the Olympic team. I get emotional talking about it now. Sitting there, hadn't showered, hadn't slept, hitchhiked out there. I pick up the paper and saw my name. I made the Olympic team. That was the first step."

Not unlike today's Concacaf qualification process, there were many challenges trying to get results in Barbados, Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, ranging from hostile crowds to enduring heat and humidity and dodgy officiating.

The U.S. reached the semifinal round and needed to defeat El Salvador at a neutral site at “The Office” in Kingston, Jamaica in 105-degree heat on Sept. 18, 1971 to advance. Messing found himself center stage during penalty kicks after the teams played to a 1-1 draw.

The tie-breaker was knotted up at 3-3, and Messing needed to find a way to deny El Salvador's Mario Castro.

"I played basketball, football, baseball, so I'm used to the psychology of freezing the guy at the free throw line, or calling a timeout before a guy is going to try and kick a field goal," he said. “That's not new to me. So there in the heat, a maniacal game, it's coming down penalty kicks. It comes down to the fifth shot.

"I had long curly hair. It was hot out. I'm sweating. I took off my shirt. I started spinning it around my head, I charged out at him. The stands were going nuts, the referee was giving me a yellow card. I just stared him in the face. I wanted to him to know he's looking at the craziest guy he's ever seen in his life. I put back on my shirt, went into the goal, and he hit it about 20 yards above the crossbar.

"We advance. If you're a goalkeeper, it's the juxtaposition of being a yogi and a train wreck. You've got to got to be a little bit crazy, but you got to be cool, calm and collected.”

For the first time since 1956, a U.S. soccer team was headed to the Olympics. Messing added that it was the first American soccer side to actually qualify for the Summer Games, as previous entrants had been invited to participate.

"Anybody who's been through a path that I have, we consider ourselves pioneers as the first U.S. team that qualifies," he said. “It was a big deal when I got home, and I was a lifeguard. I went to the swimming pool with my USA Olympic jacket on. If you're in the Olympic Games, representing your country, it's a big deal."

Since Berlin hosted the 1936 Olympics, Germany - then West Germany - was a transformed country and society.

"Berlin in 1936, at the height of Hitler and the Nazi regime. Jesse Owens, the black athlete, really showed everybody in Hitler and the Nazi regime up by showing up and winning four gold medals," Messing said. "Now, 36 years later the Olympics in Munich. The evolution was they wanted to have the greatest games. They wanted to show the best face … the new Germany. They were wonderful: the hospitality, the village, the festivities. They were insistent on putting the best face on Germany to the rest of the world, and they did that."

If you thought competing in the games was all glory, think again. Messing did not play in the USA's opening two matches.

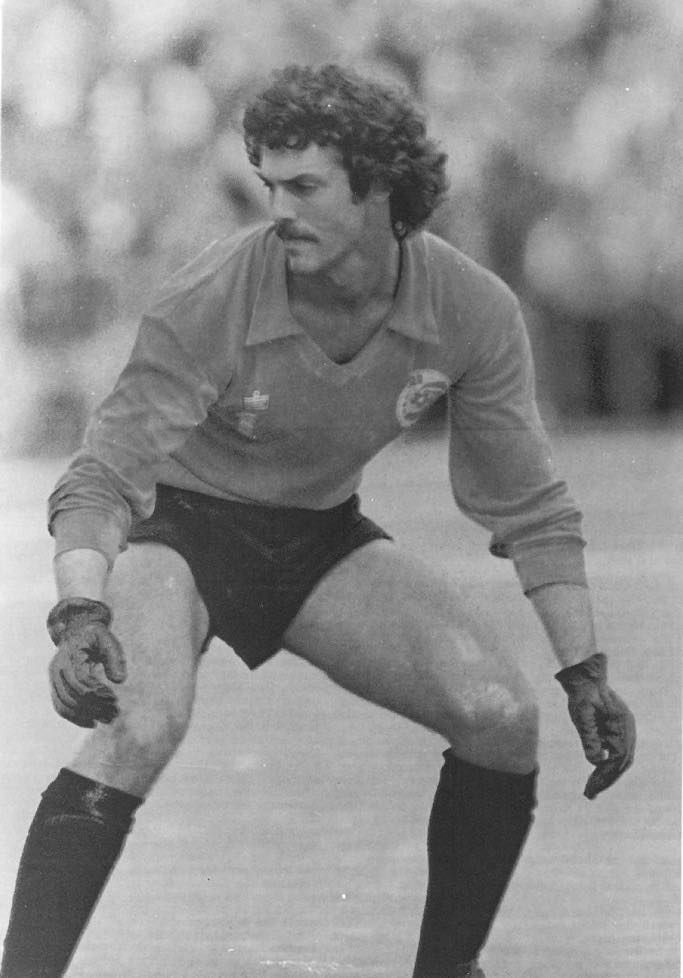

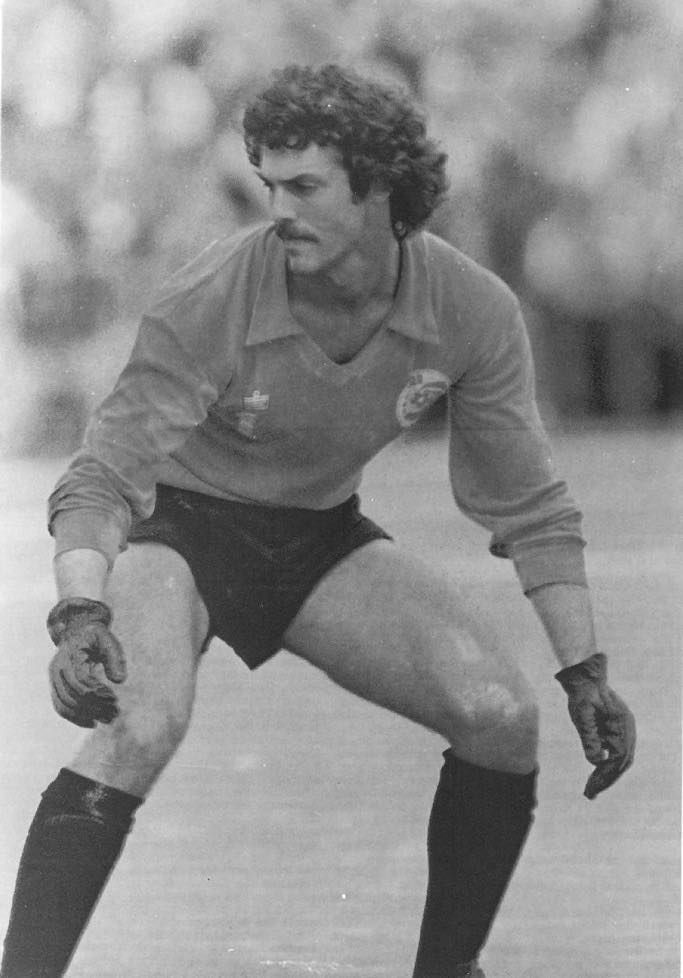

"Bob Guelker, who I love and may he rest in peace, we never got a long," he said. "I'm this long-haired mustachioed hippie from New York, he's a Midwest conservative razor cut, crew cut. So, we get to the Olympics and coach Guelker says to me, 'I've got to cut my sideburns.' I had sideburns down here."

Messing pointed to his lower cheek.

"He said, 'You're representing the country. You've got to cut your sideburns.' I said, 'Dude, I'm not cutting my sideburns. You know this is who I am. I helped get us here.' He said you got to cut your sideburns or you don't play."

Instead, Mike Ivanow backstopped the Americans in their first two Group A matches - a scoreless draw with Morocco and a 3-0 loss to Malaysia.

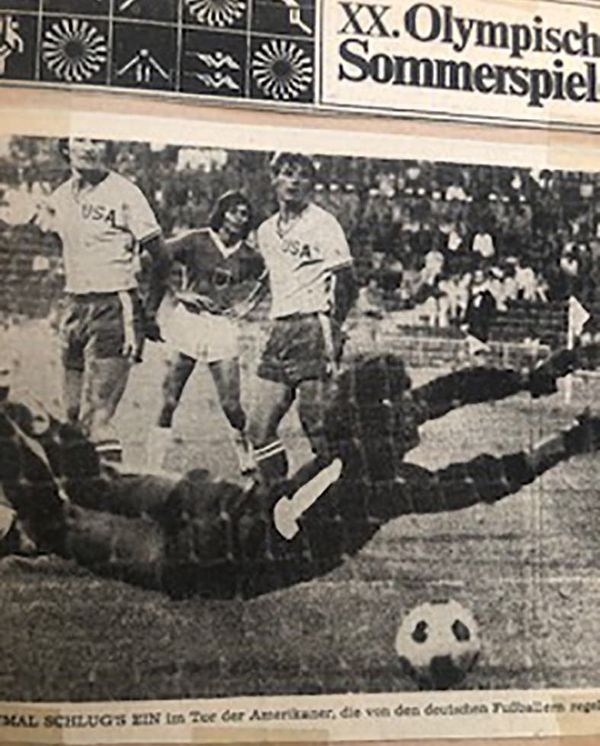

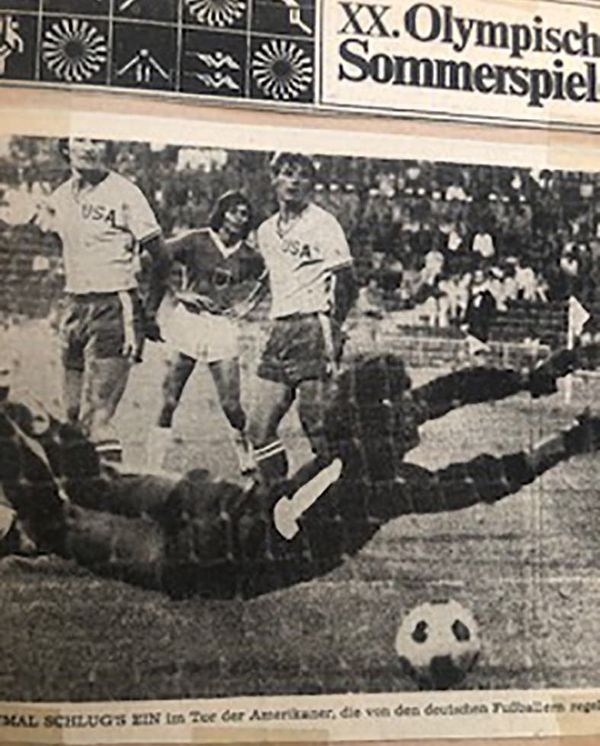

Finally, Messing got his opportunity against host and heavily favored West Germany in the final group stage match before a capacity crowd at Olympic Stadium.

"Well, thanks a lot." Messing said. "We were playing in the Munich Stadium in front of 70,000 people against really what was Bayern Munich's team. Athletes such as Uli Hoeness. The names go on and on. It was the USA, a bunch of college kids against Germany; 70,000 people. Three minutes into the game. Uli Hoeness takes a shot, breaks my nose. Bleeding, I crack it back into place. I played the whole game, and I think to this day I have two Olympic records, one for the most saves in the game - 23. I don't know how that's even possible. Unfortunately, the other record for the most goals allowed. We lost 7-0. The only time we got the ball, past midfield was when I punted it there. But we went down with a fight, and up until then, I reveled in every moment."

Messing reportedly played well, despite the conceded goals, including four by Bernd Nickel.

Despite elimination, the team got to stay in the Olympic Village, which, did not boast the world-class security.

"Every night me and some of the other athletes, men and women, we'd go into Munich, go to the beer halls, drink," Messing said. "There was no security, and the way we get back into the village, there was only one main guard gate. So, we'd be in our track uniforms. We'd scale the fence, and we'd wave at the two guys at the security booth. We're back in our rooms after curfew."

One early morning came that pounding on his room's door.

Messing and other Jewish athletes were given protection for their own safety.

If this was another time, Messing might have resisted. In the 1930s and 1940s, Jewish people were thrown into concentration camps, if not killed before that.

"It was that moment of fear," he said. "Yes, being in Germany, yes, knowing the history, yes being Jewish. When you have a rifle and machine gun pointed at you, it was another split second, I was going to strike the bigger guy."

While in protective custody, Messing followed the dreadful events.

"The horror of the terrorist attack was shown all over the world," he said. "In the end the murder of 11 Israelis. Six coaches, five athletes, including my friend David Berger, while the world watched. Jim McKay and Howard Cosell broadcast it to the world. So, it's still hard to speak about it now, and it's really a time in the history of man that we unfortunately continue to see over and over again. But it was really the first time that it had taken over and targeted a sporting event like the Olympics. I took the next plane home and my Olympic dreaming is over."

The Olympic experience didn't define Messing, now 70, but made him wiser about our complicated world. Every year in New York City here attends a “Munich 11” dinner, held in memory of the 11 Israelis who were murdered in the attack.

"I'll never forget it," he said. "I can't watch the Olympics today without that triggering the thoughts. That will never be erased from my mind. Life is how do you deal with prosperity; how do you deal with adversity. We can't redo the scene that happened in the Olympic Village in Munich. I take great joy in my professional career and my broadcasting career now, but I’ll never, never forget. And that's an expression, never forget."

The Munich Games were at the cusp of a career that has spanned almost five decades. Messing backstopped the Pele-led New York Cosmos to the 1977 North American Soccer League championship to cap off the Black Pearl's fabulous career. He played goal for the New York Arrows, who captured four successive Major Indoor Soccer League championship before he became a color commentator, mostly for the New York Red Bulls these days.

"When you have these three things on your resume or business card, you'll get the attention of anybody," Messing said. "I could probably reach anybody politically famous in the world based on three things on that card. All American, Harvard, U.S. Olympian, goalkeeper for Pele. So those three things, I'm unbelievably proud of. To some people it's the old American at Harvard. To some people, it's Pele, the goalkeeper. To more people, you're an Olympian. You're an Olympian forever."