A Quiet Revolution on Sloan’s Lake

Ohio transplant Max Fowler had a vision in 2016 of an amateur club run like a professional club – and Athletic Club of Sloan’s Lake has been moving on up in Colorado’s soccer scene ever since.

Jacob Love discovered Athletic Club of Sloan’s Lake by piling on goal after goal against them.

“We were smoking them; it wasn’t even close,” said the 28-year old Michigan-born striker, a two-time college all American and national champion. “But I loved that they seemed organized – a real team and not just a random bunch of guys like I was with.”

After that indoor game, a lopsided loss that wasn’t at all uncommon in the club’s early days, Love marched up to the Sloan’s Lake bench and asked the man in charge, Max Fowler, if he could come along to training. Fowler, who founded the club in 2016, didn’t hesitate. His answer was yes. Pretty please.

The encounter, charming and somehow backward, speaks to the appeal of this young club on the fringes of Denver that’s carving out its own little corner of Colorado’s soccer scene.

In November of 2016, shortly after Donald J. Trump was elected President of the United States, Fowler asked himself a question. What have I done to make my community better? The answer was unsatisfying to the self-described “lifetime soccer-guy” with experience coaching at college and academy level.

So he started his own club.

“I had the feeling that the men’s clubs in the area were doing things wrong,” he said of wanting to capture the social component of the ethnic clubs of his boyhood near Cleveland, Ohio. “In a place like Colorado, where team sports are way down on the list of recreation options, if you’re about winning and winning only, it’s like who cares, I’ll go climb a mountain.”

Fowler, now a stay-at-home dad in his early 40s, wanted something different. A club that could “give back” and be a “positive force.” Most importantly, he wanted his club to be “of a place.”

That place is Edgewater, Colorado – and it offered unique opportunities for an amateur team to make direct headway into the community. “Here, everyone is from somewhere else,” said the founder of a club with a cheeky identity who, after a bumpy start to life, are making waves in 2023 Open Cup Qualifying.

“This is a small place, one mile by one mile, and we can make our club look like the community – and the social connections can make the community stronger,” he said of Edgewater, where he teamed up with Joyride Brewery, the de facto meet-up spot for players and a place to hold community meet-and-greets.

The club’s social media presence was unique from the start. Fowler – who dreams of an America dotted with an infinity of amateur teams, all with distinct identities specific to their varied birthplaces – set out a clear political message. This is a club where “politics and identity matter,” he said. “I wanted to start something that would live on after I’m gone.

“We’re open to different views, but the club supports voting rights and Ukraine and women’s rights – and social policies like that,” said Fowler, who takes justifiable pride in the club’s satirical Bootroom – an in-house produced zine that pokes fun at all and sundry…mostly the club itself.

Fowler oozes a romantic notion of the game and its possibilities. “We had a real fake-it-till-you-make-it vibe early on,” he said, explaining why the barely two-year-old club on the edges of Denver hosted the 2018 UPSL national finals. “Carry yourself like a big deal and you’ll look like a big deal.”

Local players noticed what was happening. The appeal was irresistible. One of them was Jack O’Brien, a Colorado native who won a 2017 NCAA national championship at Stanford.

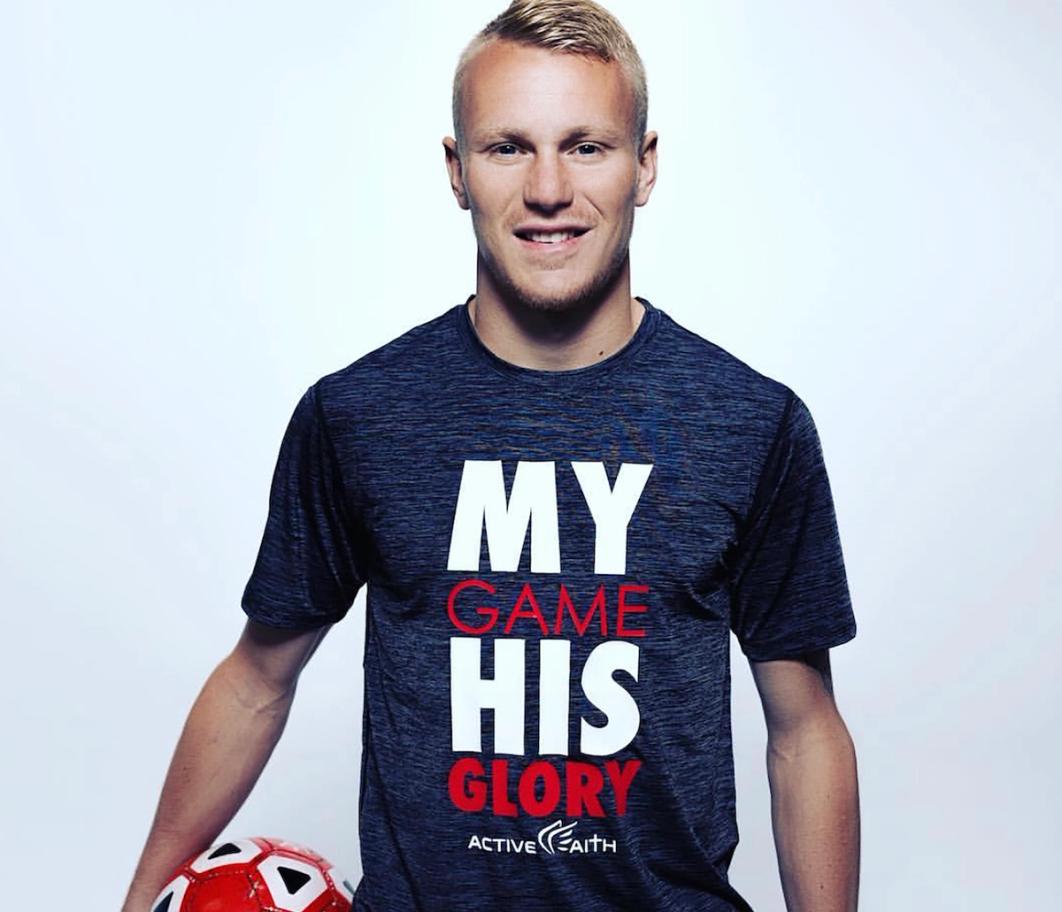

Miguel Camerolinga was another. He never went to college and works as a laborer in his dad’s construction business. And of course there’s Love, a top college player who had a season with Detroit City FC in their NISA days, and who still harbors slim hopes of a last tilt at pro ball.

“He’s gone on to become a team leader,” Fowler said of Love, who went to Italy after college to try his luck with SC Carpi. He’s an outstanding player, strong in the air and dangerous in front of goal. He links up with O’Brien and Camerolinga in a potent Sloan’s Lake attack.

The trio has helped the side rise quickly to challenge the area’s top amateur teams, like Harpos, FC Denver and Azteca – their opponent on November 19 in the Third Round of Open Cup qualifying.

Love’s goal, four minutes into second-half stoppage time against Boulder United, is the reason Sloan’s Lake is through to the penultimate round of 2023 Open Cup Qualifying. And while his more conservative politics don’t always line up with the club’s social messaging, it’s never an issue of friction.”

“It’s a setting where you don’t feel controlled,” said Love, an entrepreneur in the making who came to the Denver area to start a direct-sale business after some years away from the game in Arizona. “We have passionate debates and when it’s game-time, we all pull in the same direction.

And while the high-profile attacking trio helped the club progress from what Fowler describes as a “Rogues Gallery” in its early years, there’s contributions from all over the spectrum. The “open concept” espoused from the beginning means the team has input – and players – from all areas and backgrounds.

Goalkeeper Connor Davidson was not a college all-star. He only started playing soccer in his junior year of high school near Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He spent his college years studying – and hard.

“I found the club through a facebook ad looking for someone who could play in goal and had a pair of gloves,” laughed Davidson, who’s a rocket scientist (literally, an aerospace engineer at Blue Origin). “I hadn’t played in seven years, but Max was desperate for someone and I was vaguely the right size and shape for a goalkeeper.”

“We weren’t very good at the time,” admitted Davidson.

“I didn’t know anyone’s name yet and they didn’t know mine,” the goalkeeper laughed about his first game – against two-time Open Cup qualifiers FC Denver.

To make matters worse, Sloan’s Lake went down a man in the 15th minute. But Davidson wasn’t fazed. By luck or design, or being in the right place at the right time, he had “a crazy busy day and must have made 14 or 15 saves,” in Sloan’s Lake’s first-ever win against one of the local elites.

“The mentality we have is that we want to play high-level soccer, but we don’t attract the guys who are going to take it too seriously,” said Davidson, who’s benefitted from what Fowler sees as an “amateur team run like a professional team.”

We’d like it if you scored a hat-trick every game, but it’s more about being a good person,” added Davidson.

Fowler’s vision is taking root. Faking it early on, the club is making it now. For real. And in the Open Cup, they’re right at home in a tournament built on dreams and underdog romance.

“We’re just showing up and loving the footie,” added Davidson. “Every time I step on the field it’s more than I thought I would get [as a player] and it’s what’s making this Open Cup run so cool.

“It’s hard not to get romantic about it,” the goalkeeper added. “We’re a bunch of guys getting out there because we love it. We’re banding together and seeing results.”

#USOC2023 2QR:

— TheCup.us (@usopencup) October 16, 2022

It's unbelievable! AC Sloan's Lake scores twice late to beat Boulder United FC! JD Michael & Jacob Love with the goals to advance.@BoulderUnitedFC 1:2 @ACSloansLake

cc: @ACSLdirector pic.twitter.com/TxTytOAQvi

Fowler's vision, lofty and fun and not taking itself too seriously, survived a recent mortal threat. In July, after Fowler moved to the East Coast, the club was on the verge of folding.

To the founder’s great delight, his players stepped up.

“The players seized the means of production,” laughed Fowler, now owner/facilitator-at-large for the club he founded. “They had their own little socialist revolution. They said: We value this, we like it here. We want to keep it. So they divided the work and kept it going.”

Fontela is editor-in-chief of usopencup.com. Follow him at @jonahfontela on Twitter.