CLICK HERE to help the Philadelphia Ukrainian Nationals and the United Ukrainian American Relief Committee with humanitarian aid in Ukraine.

They closed their eyes so images of Edison Field, near the corner of 29th and Clearfield, south of Allegheny Avenue, could sharpen like ships on a foggy horizon. To remember back when men in suits, hats and raincoats took their wives out to cheer on their favorite Philadelphia sports team.

It wasn’t the Phillies or the Eagles or the 76ers they went to see. It was Tryzub – the Ukrainian Nationals, Philadelphia Ukrainians or simply the Ukes [yoo-kees] – America’s best soccer team of the 1960s.

“We beat everybody back then,” said the late Alexandre Alex Ely in 2019 about the club, comprised primarily of immigrants with roots in Ukraine who’d fled Soviet aggression between the last century’s World Wars.

Ely, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 83, spoke in a gravelly voice. He wore the fleece jacket he was given upon his induction into the National Soccer Hall of Fame in 1997. “I’ve lost track of how many trophies we won in those years,” he said. “But we had the best soccer team in the country for a good few years.”

Young Alex learned the game of soccer, futebol, playing barefoot in the crowded street games around Mogi das Cruzes in his birth city of São Paulo, Brazil. He was 12 years old the first time he wore a pair of proper soccer boots, and the lessons he learned early were a mish-mash of the jogo bonito of Brazilian lore and the blood-and-thunder of its reality.

Those lessons served him well after his arrival in the U.S., on his own and still a teenager, in 1959.

“There’s nothing romantic about playing soccer, especially in those days,” said Ely with a rough laugh, remembering the broken collarbones and shattered ankles that kept him out of the Ukrainian Nationals starting XI (those were the only things that kept him out).

“It was very dangerous playing in those days. Guys would go after you hard. But there was something inside me that never let me give up and we always seemed to win,” added Ely, who earned four caps for the U.S. Men’s National Team, including a World Cup qualifying loss in Mexico in 1960.

His teammate from those old days, Ivan John Barodiak, who came to the club from Argentina’s San Lorenzo, remembered things the same way: “The game was really rough and it was a lot more difficult to show your finesse because there was always someone looking to kick you. It was hard to play soccer the right way, but we did.”

Winning became a habit in those old Ukrainian Nationals teams. They won four Open Cups, six American Soccer League (ASL) titles and two Lewis Cups (The ASL’s league Cup).

What Ely remembered best is the way they played the game. “I was kind of a tough nut in middle-field, but I liked to deliver the goals to my teammates,” said the man who returned to Brazil in 1965 to play for Santos, even lining up beside the legendary Pele on a few occasions. “We liked to keep the ball and move it around the field, which was crazy then. Most teams had the ball up in the air all the time.”

Borodiak, now 82, was a cultured fullback and another club legend who played from 1963 to 1966. He recalled the Ukes’ approach the same way. “The idea was to connect with each other,” said the defender, who went on to play in the early days of the old North American Soccer League (NASL) with the Baltimore Bays and Cleveland Stokers before going into business making porcelain bridges for the dental industry.

“No one was supposed to be involved with the ball too long,” added Barodiak, whose parents left Ukraine in the turbulent 1930s. “In this country, we were able to stand above our opponents by keeping and moving the ball around the field.”

That possession game also helped the Ukes when big-name teams from abroad came over for friendlies -- which they often did. Manchester United, Wolves, Eintracht Frankfurt, VFB Stuttgart, Austria Vienna and Man City were just a few of the foreign teams to take on the Ukrainian Nationals through those glory years. Silken gameday banners commemorating those meetings still hang in the barroom of the club headquarters in Horsham, PA -- which doubles as a museum of Ukrainian-American sports history.

“We used to get two, three thousand people to regular league games,” said Bogdan Siryj, the former club president. He was a young boy back in the 60s and he watched his favorite players, like Ely, Borodiak and Mike Noha (who famously scored five goals in an Open Cup final) up close at Edison Field. “The enthusiasm was incredible and these guys were my heroes. We used to carry [Mike] Noha around the field on our shoulders.”

It’s hard for Siryj – hard for all the old Ukrainians – not to choke up when they recalled the old days. The Open Cup Final of 1964 required 90 minutes of extra-time after 90 minutes of regular time. “It’s one of the longest games ever played,” laughed Ely with a shake of his head.

There were the ‘double’ years of 1961 and 1963. And the four Open Cup titles won in the space of six years (1960-1966). The Ukes, such was their appeal, became the first soccer team in American history to have their home games televised.

“So many people used to talk about our games and the players,” remembered George Litynsky, a goalkeeper who was scouted in his adoptive home of Argentina. “There was a bar [on Broad Street] and people used to show up there and hang around and talk about us. There was so much excitement around the club. And for me, when I came, I had almost no English, but these people around me were like a family.”

Litynsky came late in the wave of Ukes’ dominance, but his memories of the 1966 Open Cup Final remain fresh. He was back-up that day to Tarnawsky, born in the former USSR and once an Argentinian international and pro with Newell’s Old Boys.

“We had close to 4,000 fans here,” said Litynsky who went on to have a career in architecture. “We had beaten them [Orange County FC] 1-0 in California and then we beat them 3-0 in Philly, and I can still remember how much enthusiasm there was at the field and how the fans ran on the pitch after the final whistle.”

It wasn’t always easy. In those days, the best soccer team in America was still semi-pro.

“The money wasn’t good,” Litynsky laughed. “I was getting 40 dollars a game. Some of the superstars like Tarnawksy and Borodiak, maybe they got 60 dollars a game. But it wasn’t like it is today with contracts for millions of dollars. We all used to play and we all used to work.”

What the old Ukes remembered sharpest were the winning moments, those ones that never seem to dull. Of being the best, of being young and surrounded by possibility.

“It was something; the way people would come from far away, from Delaware and farther than that, to watch us,” said Ely.

Borodiak remembered the wide smiles after the final whistle, before the trophy came, when they’d done enough to win. “It’s most memorable when you become a champion,” he said in his halting accented English. “The leagues and the cups -- you remember those moments like they were yesterday.”

For Litynsky, it’s simpler than all that: “It felt like home.”

It was a long day for the old-timers – legends who dressed for the occasion in blue blazers, pressed shirts and hard shoes. They returned to their wives and grown children who waited patiently, sipping drinks below a flock of trophies, like birds, in the rafters.

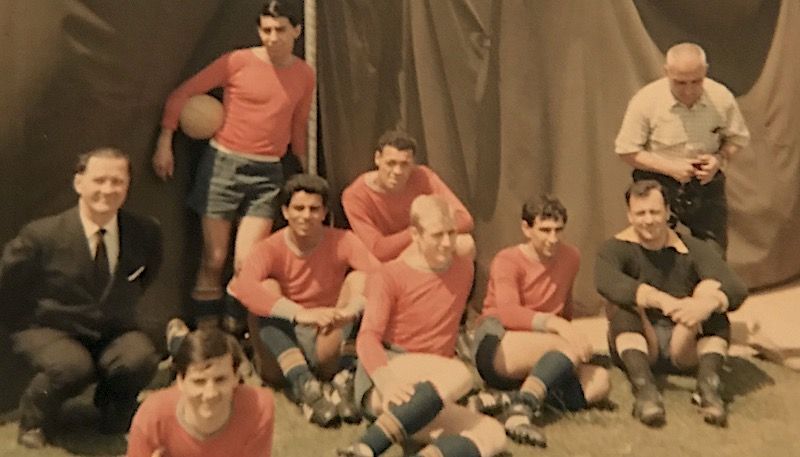

These champions shook hands and said so-longs in a barroom with pictures of their younger selves, black-and-white and ropy with muscle, hung on the walls around them.

CLICK HERE to help the Philadelphia Ukrainian Nationals and the United Ukrainian American Relief Committee with humanitarian aid in Ukraine.